I've no idea whether Tidal, the paid-for music streaming service that's being fronted by Jay-Z, will turn out to be a winner or will quietly fade away like so many other digital music initiatives before it, but one thing I do know.

There's a fundamental problem with using performers as the public face of this kind of enterprise. The musicians who are famous enough to front such a launch are more famous for their wealth than their music. Many seem to have spent the last few years flaunting it.

There they all were lining up in New York yesterday: Rihanna, Madonna, Kanye West, Jack White, Usher, Beyonce, Daft Punk, Arcade Fire and similar. All of these people have been huge winners in their particular areas of the market. The key lesson of the internet is the Google lesson. The winner takes it all. There's very little left for anyone else.

Most people looking at that line-up of millionaires will find it hard to take them seriously as poster boys for starving artists. The people who are really suffering in the new digital dispensation are the ones not famous enough to be on that stage.

"World-class thinking about music, business, publishing and the general world of media" - Campaign

chaplin

Tuesday, March 31, 2015

Monday, March 30, 2015

No point hiring image consultants if your own receptionist is letting you down

Piece in FT by Lucy Kellaway about how much you can tell about a visitor from the way they deal with a receptionist. All true. By the same token that visitor can also tell a lot about a company by the way the receptionist behaves.

I regularly sit in reception in a building used by one very high-profile public body and never fail to be amazed by the gossip and parochial whinging the staff seem content to let me overhear.

Kellaway talks about a company who have a spy among their reception staff whose job it is to report on the behaviour of waiting job candidates. Some managements should have a spy among the people waiting. They might find out a few things about their public image that would horrify them.

I regularly sit in reception in a building used by one very high-profile public body and never fail to be amazed by the gossip and parochial whinging the staff seem content to let me overhear.

Kellaway talks about a company who have a spy among their reception staff whose job it is to report on the behaviour of waiting job candidates. Some managements should have a spy among the people waiting. They might find out a few things about their public image that would horrify them.

Saturday, March 28, 2015

I've had it with social kissing - I'm going back to shaking hands

Interesting Marsha Shandur should make a little video advising women how to take evasive action when a male colleague moves in for a peck on the cheek in a business or social situation. Interesting because I suspect the man moving in was only doing it from a mistaken sense of gentlemanly obligation.

Ideally we'd restrict the hugging to the female colleagues who are clearly friends but it's never easy to draw that line, particularly in a group situation. If the two other men at the gathering have "gone in" it would be ungallant not to follow.

Since the whole world turned luvvie and it became impolite not to pretend that everyone is our best friend, there's a growing tendency to view formality as coldness. It's got to the point where men would rather be accused of being too familiar than of being too distant or - ridiculous as it may sound - somehow "anti-women. The men are just trying to be au courant. That's why women are having to do so much fending-off.

I don't have any solution to this problem other than standing back, looking ill-at-ease and proferring a firm hand to shake. If she wants more than that, it's Ladies Choice.

Since the whole world turned luvvie and it became impolite not to pretend that everyone is our best friend, there's a growing tendency to view formality as coldness. It's got to the point where men would rather be accused of being too familiar than of being too distant or - ridiculous as it may sound - somehow "anti-women. The men are just trying to be au courant. That's why women are having to do so much fending-off.

I don't have any solution to this problem other than standing back, looking ill-at-ease and proferring a firm hand to shake. If she wants more than that, it's Ladies Choice.

Friday, March 27, 2015

No man but a blockhead ever blogged, except for the remote chance of an award

This week I was talking about blogging to people on a writing course run by The Oldie. I asked if any of them had ever considered blogging. Only one had and it turned out she'd given up after a few entries. I told the rest that if they'd got this far without it they probably didn't need to start now. Only those with a need to say their piece so intense it almost qualifies as an illness should even think about blogging.

Somebody asked if you could make any money from it. I said no. He then came back with a blogging spin on the old Samuel Johnson line about none but a blockhead ever having written except for money. He was quite militant about it. It's odd how people can get so concerned about other people doing things for no other reason than they feel like it. The people I've met who are most vehement in their condemnation of Twitter tend to be people who don't use it and therefore don't see why anybody else should. This seems short-sighted. I don't much like Facebook but I understand why it's popular.

I started this blog in 2007 out of curiosity and vanity. I've just looked at the first post, which was about how redundant the singles chart is. Funnily enough, I've just written a variant on the same theme for The Guardian. I came to the conclusion years ago that it was a complete waste of time trying to get commissioning editors interested in ideas and you're better off getting them off your chest by just making them blog posts.

Blogging is my self-indulgence. It's easier than a diary and cheaper than therapy. And sometimes people read it. Some posts are more popular than others, which is when my publisher's instincts kick in and I think "I should do more of that kind of thing", which is obviously a snare and a delusion. If people like it, that's because they like the self-indulgence of it.

And now it's even more hilarious because I'm on the shortlist for the Blogger of the Year at the London Press Club Awards. So maybe that's why I started doing it. I knew there'd be the outside chance of glory in it some day.

Somebody asked if you could make any money from it. I said no. He then came back with a blogging spin on the old Samuel Johnson line about none but a blockhead ever having written except for money. He was quite militant about it. It's odd how people can get so concerned about other people doing things for no other reason than they feel like it. The people I've met who are most vehement in their condemnation of Twitter tend to be people who don't use it and therefore don't see why anybody else should. This seems short-sighted. I don't much like Facebook but I understand why it's popular.

I started this blog in 2007 out of curiosity and vanity. I've just looked at the first post, which was about how redundant the singles chart is. Funnily enough, I've just written a variant on the same theme for The Guardian. I came to the conclusion years ago that it was a complete waste of time trying to get commissioning editors interested in ideas and you're better off getting them off your chest by just making them blog posts.

Blogging is my self-indulgence. It's easier than a diary and cheaper than therapy. And sometimes people read it. Some posts are more popular than others, which is when my publisher's instincts kick in and I think "I should do more of that kind of thing", which is obviously a snare and a delusion. If people like it, that's because they like the self-indulgence of it.

And now it's even more hilarious because I'm on the shortlist for the Blogger of the Year at the London Press Club Awards. So maybe that's why I started doing it. I knew there'd be the outside chance of glory in it some day.

Thursday, March 26, 2015

Fifty years late, here's my review of "Highway 61 Revisited"

It's all about the fear of falling. By 1965 Bob Dylan had become famous and celebrated more quickly than anyone else. Like anyone suddenly famous and celebrated, he had a secret fear of being found out.

Most of us just have dreams about having to go for job interviews without clothes. Songwriters put the same fear into songs.

I realised this last night listening to a pristine mono copy through a top-of-the-range hi-fi in the library at the Barbican.

Side one starts with "Like A Rolling Stone", pop's best take on what it must be like to fall from grace. Side two starts with "Queen Jane Approximately", which is about being shunned by those on whom you previously depended. Both songs are supposedly about other people. But Dylan knew their falls might foreshadow his own. The failings we point out in others are often the same ones we don't like to recognise in ourselves.

In 1965 only disgraced cabinet ministers seemed to care about prestige and shame. In the age of social media we all do. That's one of the reasons these songs are even more powerful now.

At the same time the music feels as if it's on the verge of falling apart. The musicians are never comfortable and on top of things. You can almost hear their eyes swivelling from side to side as they try to keep track of the chord shapes, wonder whether each verse is the last and whether what they're doing is what's required.

Somebody pointed out that until last night he'd never heard the tambourine part on "Like A Rolling Stone" and how strange and haphazard it seemed to be. It's that very uncertainty that keeps the music so alive. "Highway 61 Revisited" isn't perfect, which is one of the reasons why it's still brilliant.

Most of us just have dreams about having to go for job interviews without clothes. Songwriters put the same fear into songs.

I realised this last night listening to a pristine mono copy through a top-of-the-range hi-fi in the library at the Barbican.

Side one starts with "Like A Rolling Stone", pop's best take on what it must be like to fall from grace. Side two starts with "Queen Jane Approximately", which is about being shunned by those on whom you previously depended. Both songs are supposedly about other people. But Dylan knew their falls might foreshadow his own. The failings we point out in others are often the same ones we don't like to recognise in ourselves.

In 1965 only disgraced cabinet ministers seemed to care about prestige and shame. In the age of social media we all do. That's one of the reasons these songs are even more powerful now.

At the same time the music feels as if it's on the verge of falling apart. The musicians are never comfortable and on top of things. You can almost hear their eyes swivelling from side to side as they try to keep track of the chord shapes, wonder whether each verse is the last and whether what they're doing is what's required.

Somebody pointed out that until last night he'd never heard the tambourine part on "Like A Rolling Stone" and how strange and haphazard it seemed to be. It's that very uncertainty that keeps the music so alive. "Highway 61 Revisited" isn't perfect, which is one of the reasons why it's still brilliant.

Monday, March 23, 2015

I don't know about the future of the music press but its past gets better all the time

A questionnaire about the future of the music press was doing the rounds online this weekend. "Do you get most of your information about music from press or from blogs?" That kind of thing. I stopped filling those in a while ago. They're mostly sent by journalism students hoping they can turn their dissertation into a gig. I tell them the gig's gone but they want to believe that's not true so badly that they try to reason the music press back into rude health.

A questionnaire about the future of the music press was doing the rounds online this weekend. "Do you get most of your information about music from press or from blogs?" That kind of thing. I stopped filling those in a while ago. They're mostly sent by journalism students hoping they can turn their dissertation into a gig. I tell them the gig's gone but they want to believe that's not true so badly that they try to reason the music press back into rude health.They'd be better off reading a couple of new memoirs about rock journalism from the days when the living was easy and the cotton was high. Shake It Up Baby! is by Norman Jopling and it's sub-titled "notes from a pop music reporter 1961-1972".

For instance, in the week of May 15th 1965 Norman's in the Savoy with The Beatles who've come to see Bob Dylan. They go to the restaurant and order porridge and pea sandwiches. Paul sings their new single "Help!" to him and says "I think John and I are writing different sorts of songs now....I can't say whether they're better or worse but they're certainly different."

The other book is Another Little Piece of My Heart: My Life of Rock and Revolution in the '60s by Richard Goldstein, who was the man who wrote the "Pop Eye" column in the Village Voice and therefore has a claim to be the world's first rock critic. By the late sixties the chummy tone of Norman Jopling's articles in the Record Mirror had given way to something altogether more knowing.

For instance, Goldstein remembers talking to Jimi Hendrix in New York in 1970. "Hendrix was stupefied, his shirt stained with what looked like caked puke. There was no publicist to make excuses or even wipe him up."

There's nothing quite as seedy as the Hendrix encounter or as epochal as dinner with the Beatles in Mark Ellen's Rock Stars Stole My Life!: A Big Bad Love Affair with Music, which has just come out in paperback, but there is a vivid and some say quite amusing account of what it was like to work for NME, Smash Hits, Q and the rest when the business was exploding in every direction. In some senses that was the best era of all. I would say that, wouldn't I?

Mark and I are talking to Richard Goldstein and Norman Jopling at next Tuesday's Word In Your Ear at the Islington. Anybody with even a passing interest in what it was like when the going was good really ought to be there.

Meanwhile, here's Richard interviewing Jim Morrison in 1969.

Thursday, March 19, 2015

How Lambert and Stamp and the Who made it up as they went along

Chris Stamp was the brother of Terence, the film star. Kit Lambert was the son of Constant, the celebrated classical musician.

They met in the film business of the early sixties. They got into music to further their film careers. They reckoned that the only way they could get a seat at the table when movie deals were made was by coming along with their own pop group who wrote their own material. That's how they found The Who.

They signed the group by promising to pay them a weekly wage. The Who's parents were very impressed by the weekly wage. Lambert and Stamp didn't know much about the music business but they managed to keep the weekly wage coming long enough to inspire the group. Lambert encouraged Townshend to write long-form pieces that could be performed in concert halls. Stamp showed the group how to carry themselves.

By the time they came to record "Who's Next" in 1971 Lambert and Stamp were so deep in drink and drugs that the group had to take care of themselves. Lambert never quite sobered up and died in 1981. Stamp eventually got straight and has made his peace with The Who, peace enough for them to be featured in a fascinating little documentary about their unique relationship with the group.

Because they were film guys the footage of the group they shot back in the days is surprisingly beautiful. So beautiful, in fact, that it looks almost artificial. The best bit is Townshend and Daltrey sitting together doing what they never did back in the day, which is actually discuss the tensions within the group. Like all the survivors of the sixties they look back in amazement at the things you could get away with in those days just before everybody learned how to be professional.

They met in the film business of the early sixties. They got into music to further their film careers. They reckoned that the only way they could get a seat at the table when movie deals were made was by coming along with their own pop group who wrote their own material. That's how they found The Who.

They signed the group by promising to pay them a weekly wage. The Who's parents were very impressed by the weekly wage. Lambert and Stamp didn't know much about the music business but they managed to keep the weekly wage coming long enough to inspire the group. Lambert encouraged Townshend to write long-form pieces that could be performed in concert halls. Stamp showed the group how to carry themselves.

By the time they came to record "Who's Next" in 1971 Lambert and Stamp were so deep in drink and drugs that the group had to take care of themselves. Lambert never quite sobered up and died in 1981. Stamp eventually got straight and has made his peace with The Who, peace enough for them to be featured in a fascinating little documentary about their unique relationship with the group.

Because they were film guys the footage of the group they shot back in the days is surprisingly beautiful. So beautiful, in fact, that it looks almost artificial. The best bit is Townshend and Daltrey sitting together doing what they never did back in the day, which is actually discuss the tensions within the group. Like all the survivors of the sixties they look back in amazement at the things you could get away with in those days just before everybody learned how to be professional.

Wednesday, March 18, 2015

My favourite Andy Fraser band wasn't Free

When I heard Andy Fraser had died I got out this album, "First Water" by Sharks. It didn't disappoint.

Sometimes it seems every band from the 70s has some kind of cult following. But not Sharks.

There's been no loving reissue programme for Sharks, no retrospective in Uncut, no young movie actor has stepped forward to claim them as his own. They're not on Spotify and there's barely anything on You Tube. It seems the only people who know anything about them are the people who saw them.

In the wake of the death of Fraser people are rightly talking about Free, the band he was in before forming Sharks. They're the band with all the hits. Sharks were a slightly less ingratiating, slightly more "indie" (to use a word that nobody used at the time) outlet for Fraser's still teenage instincts.

Fraser formed Sharks in 1972 with Marty Simon, a drummer from Canada, recruited Britain's most versatile session guitarist Chris Spedding and probably thought he'd have a shot at being his own front man. But the record company didn't rate his voice and brought in Snips as singer.

That probably explains why he left when their first album "First Water" came out in 1973 and failed to set the world on fire. They made another one which isn't anything like as good and then split up.

I saw Sharks three times before Fraser left and they made one of the best rackets I've ever heard in my life. They made music which had some of the more appealing characteristics of the jam - that sense of a groove being mined to see what might be inside it and the feeling of edges which nobody could be bothered to polish - allied to that catchiness which hints at further layers of catchiness to come.

Like most great rock and roll bands they were led from the rear by the rhythm section, nobody in the band was actually playing what you were hearing and the guitar solos were largely implied.

Sometimes it seems every band from the 70s has some kind of cult following. But not Sharks.

There's been no loving reissue programme for Sharks, no retrospective in Uncut, no young movie actor has stepped forward to claim them as his own. They're not on Spotify and there's barely anything on You Tube. It seems the only people who know anything about them are the people who saw them.

In the wake of the death of Fraser people are rightly talking about Free, the band he was in before forming Sharks. They're the band with all the hits. Sharks were a slightly less ingratiating, slightly more "indie" (to use a word that nobody used at the time) outlet for Fraser's still teenage instincts.

Fraser formed Sharks in 1972 with Marty Simon, a drummer from Canada, recruited Britain's most versatile session guitarist Chris Spedding and probably thought he'd have a shot at being his own front man. But the record company didn't rate his voice and brought in Snips as singer.

That probably explains why he left when their first album "First Water" came out in 1973 and failed to set the world on fire. They made another one which isn't anything like as good and then split up.

I saw Sharks three times before Fraser left and they made one of the best rackets I've ever heard in my life. They made music which had some of the more appealing characteristics of the jam - that sense of a groove being mined to see what might be inside it and the feeling of edges which nobody could be bothered to polish - allied to that catchiness which hints at further layers of catchiness to come.

Like most great rock and roll bands they were led from the rear by the rhythm section, nobody in the band was actually playing what you were hearing and the guitar solos were largely implied.

Monday, March 16, 2015

Everything worthwhile I know I learned by heart

Every week there's a story on the news agenda which is so stupid you just know it's not worth finding out about. Last week there was something about a kitchen. Don't go any further. I don't wish to know.

This week there are poets arguing about the value of kids learning things by heart. I'm sure poets aren't stupid enough to say that this is ever a bad idea. I'm equally sure there are hacks capable or twisting their words to make it look as though they did. And I'm certain the BBC will have staged one of those sham debates where somebody who's in favour of fresh air has been put up against somebody who thinks it's bad for you.

I took a little notice of this because recently I've tried to teach myself to learn a few bits of Shakespeare off by heart. I used to be able to do this when I was young and I was interested to see if I still could, particularly now that Google's causing my mental muscles to atrophy.

I also did it as an alternative to reading while on the tube or listening to music while out walking. I'm enjoying the process. I'll be the one sitting opposite you staring into space with lips barely moving, stopping occasionally to check the lines on my phone.

Everything worthwhile I know I learned by heart.

This week there are poets arguing about the value of kids learning things by heart. I'm sure poets aren't stupid enough to say that this is ever a bad idea. I'm equally sure there are hacks capable or twisting their words to make it look as though they did. And I'm certain the BBC will have staged one of those sham debates where somebody who's in favour of fresh air has been put up against somebody who thinks it's bad for you.

I took a little notice of this because recently I've tried to teach myself to learn a few bits of Shakespeare off by heart. I used to be able to do this when I was young and I was interested to see if I still could, particularly now that Google's causing my mental muscles to atrophy.

I also did it as an alternative to reading while on the tube or listening to music while out walking. I'm enjoying the process. I'll be the one sitting opposite you staring into space with lips barely moving, stopping occasionally to check the lines on my phone.

Everything worthwhile I know I learned by heart.

Thursday, March 12, 2015

Did Marvin Gaye actually write "Got To Give It Up"? Up to a point.

Lots of interesting things came out of the Marvin Gaye/Pharrell Williams court case.

There's the $32 million the track is said to have earned, which indicates that today's big hits are bigger than ever.

There's Robin Thicke's admission that he had no part in writing the song, despite having his name among the composer credits. (All the big hits today are written by teams. The artist's name is generally included, though it's impossible to know how much part they play in coming up with it. One very famous superstar is known as "add a word, take a third".)

There's a good piece here from today's New York Times which argues that the whole case is based on a way of looking at the world that no longer applies. One of the point it makes is as follows: "Implicit in the premise of the case is that Mr Gaye's version of songwriting is somehow more serious than what Mr Williams does, since it is the one that the law is designed to protect".

I'll go further. "Mr Gaye's version of songwriting" was probably nothing like we think it was. For a start "Got To Give It Up", the song that was allegedly copied, was never actually written. It was recorded from various jams, often surreptitiously, by Marvin Gaye's engineer Art Stewart, who is quoted in David Ritz's Marvin Gaye biography "Divided Soul" saying "Marvin wasn't sure of what I was doing but he left me alone to piece the song together. On Christmas Day, 1976, after working on it for months, I ran it over to his house. He liked it but still wasn't sure - a typical Marvin reaction."

We'll never know how true that recollection is but it certainly chimes with other accounts of how Marvin Gaye made records. He had to work through other musicians and producers because he didn't have the know-how to make a track on his own and in those days the technology still required specialist operators. And he could never make up his mind about anything.

He used to complain that Motown never paid him properly for his efforts. The musicians he worked with used to mutter the same thing about him. God knows what they think of all this money going to his children, who certainly had nothing to do with it.

There's the $32 million the track is said to have earned, which indicates that today's big hits are bigger than ever.

There's Robin Thicke's admission that he had no part in writing the song, despite having his name among the composer credits. (All the big hits today are written by teams. The artist's name is generally included, though it's impossible to know how much part they play in coming up with it. One very famous superstar is known as "add a word, take a third".)

There's a good piece here from today's New York Times which argues that the whole case is based on a way of looking at the world that no longer applies. One of the point it makes is as follows: "Implicit in the premise of the case is that Mr Gaye's version of songwriting is somehow more serious than what Mr Williams does, since it is the one that the law is designed to protect".

I'll go further. "Mr Gaye's version of songwriting" was probably nothing like we think it was. For a start "Got To Give It Up", the song that was allegedly copied, was never actually written. It was recorded from various jams, often surreptitiously, by Marvin Gaye's engineer Art Stewart, who is quoted in David Ritz's Marvin Gaye biography "Divided Soul" saying "Marvin wasn't sure of what I was doing but he left me alone to piece the song together. On Christmas Day, 1976, after working on it for months, I ran it over to his house. He liked it but still wasn't sure - a typical Marvin reaction."

We'll never know how true that recollection is but it certainly chimes with other accounts of how Marvin Gaye made records. He had to work through other musicians and producers because he didn't have the know-how to make a track on his own and in those days the technology still required specialist operators. And he could never make up his mind about anything.

He used to complain that Motown never paid him properly for his efforts. The musicians he worked with used to mutter the same thing about him. God knows what they think of all this money going to his children, who certainly had nothing to do with it.

Wednesday, March 11, 2015

The three lots of people who will miss Jeremy Clarkson on Top Gear

If this proves to be the end of the road for Jeremy Clarkson and Top Gear then it will leave a hole in the lives of three distinct sets of people.

First of all, there are the people who love him and the programme and never miss it.

Then there are the people like me who miss it all the time but rather enjoy it when we happen to catch it.

But the people who will miss him most of all are the ones who hate him and seem to use him as a handy instrument to calculate their position on the attitudinal spectrum.

The first set of people will follow him to whichever broadcaster puts most money in his pocket.

The second set will catch him even less frequently and will be dimly aware that it isn't quite the same on another channel.

The third lot will be desolated and will have to go hunting for somebody else to disapprove of, which is getting harder and harder in a BBC gelded by Compliance Culture.

Clarkson's a proper TV personality but what made his shtick work was that he was doing it on the BBC.

Not only did that give him access to the biggest audiences and, thanks to BBC Worldwide's success in selling the brand, the biggest budgets, it also gave his stunts a legitimacy they wouldn't have had anywhere else and at the same time made it seem that he was just about, by the skin of his teeth, getting away with something he shouldn't be getting away with.

Guys like Clarkson are always on the points of being fired. That's their standard operating position. Wherever you paint the line, they go and stand just six inches the other side of it. It's a way of proving to themselves that they are who everybody seems to think they are. The downside is they get fired from time to time. It's the cost of doing business.

In the case of Clarkson and Top Gear that firing would be very costly and messy for both parties because they've built the brand around him. Stories of actual or threatened punch-ups suggest that the relationship was reaching its natural end anyway. The problem is that people no longer do the natural thing, which is just walk away. TV shows nowadays can make so much money in syndication that they're kept going long after their energy has run out.

Much like rock bands.

First of all, there are the people who love him and the programme and never miss it.

Then there are the people like me who miss it all the time but rather enjoy it when we happen to catch it.

But the people who will miss him most of all are the ones who hate him and seem to use him as a handy instrument to calculate their position on the attitudinal spectrum.

The first set of people will follow him to whichever broadcaster puts most money in his pocket.

The second set will catch him even less frequently and will be dimly aware that it isn't quite the same on another channel.

The third lot will be desolated and will have to go hunting for somebody else to disapprove of, which is getting harder and harder in a BBC gelded by Compliance Culture.

Clarkson's a proper TV personality but what made his shtick work was that he was doing it on the BBC.

Not only did that give him access to the biggest audiences and, thanks to BBC Worldwide's success in selling the brand, the biggest budgets, it also gave his stunts a legitimacy they wouldn't have had anywhere else and at the same time made it seem that he was just about, by the skin of his teeth, getting away with something he shouldn't be getting away with.

Guys like Clarkson are always on the points of being fired. That's their standard operating position. Wherever you paint the line, they go and stand just six inches the other side of it. It's a way of proving to themselves that they are who everybody seems to think they are. The downside is they get fired from time to time. It's the cost of doing business.

In the case of Clarkson and Top Gear that firing would be very costly and messy for both parties because they've built the brand around him. Stories of actual or threatened punch-ups suggest that the relationship was reaching its natural end anyway. The problem is that people no longer do the natural thing, which is just walk away. TV shows nowadays can make so much money in syndication that they're kept going long after their energy has run out.

Much like rock bands.

Tuesday, March 10, 2015

Celebrating the sixties at Word In Your Ear

|

| Me, Ashley Hutchings, Mick Houghton, Simon Nicol and Mark. |

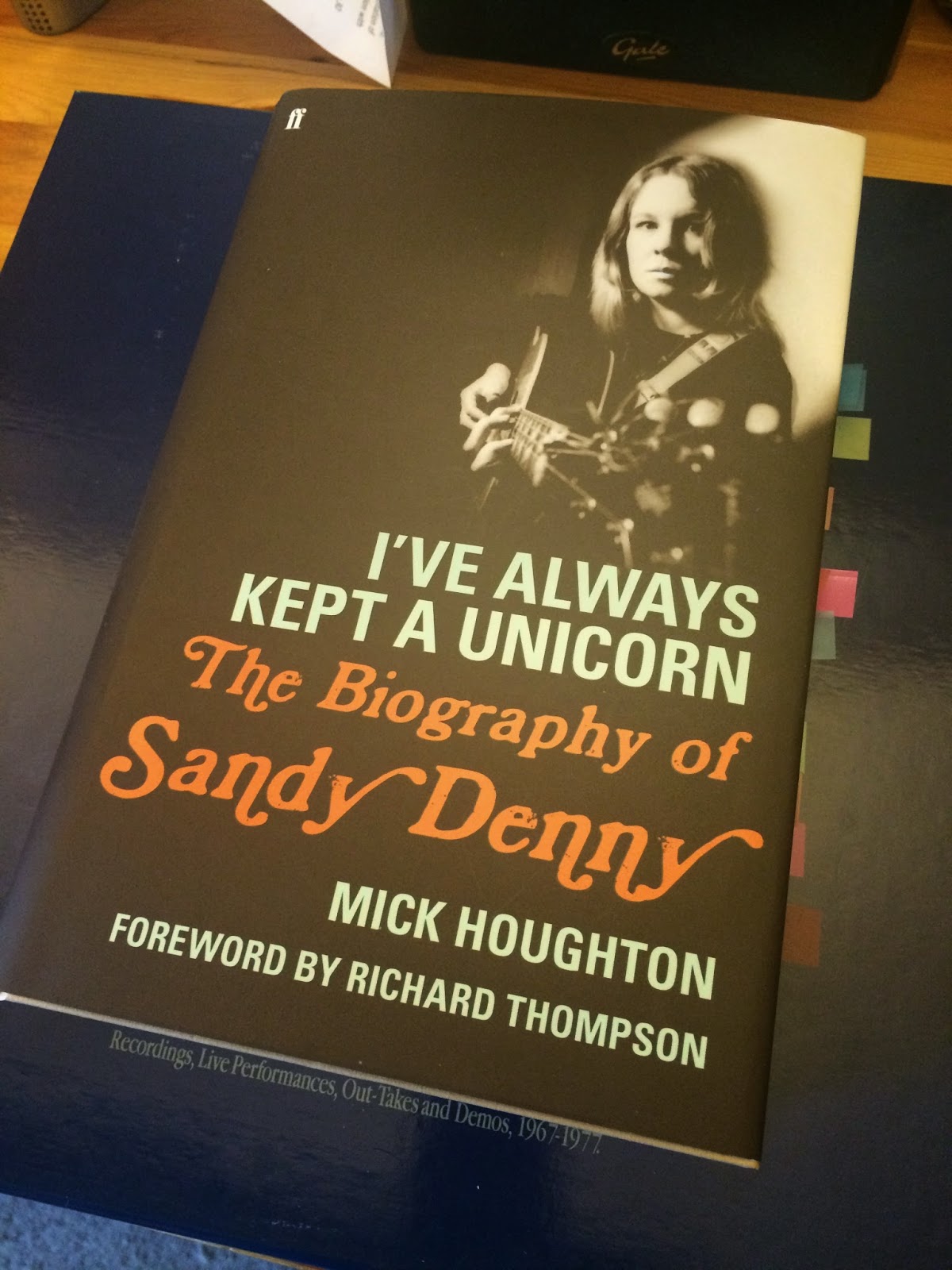

They were there to talk about Sandy Denny, who's the subject of Mick Houghton's excellent new book I've Always Kept a Unicorn: The Biography of Sandy Denny. The person who emerged from their recollections and Mick's researches was absurdly talented, confident but insecure, occasionally exasperating but not a diva.

If you want to make sure you hear the podcast, which will be published later this week, go to www.wordpodcast.co.uk and sign up.

Our next Word In Your Ear is back at the Islington on March 31st and it's a Sixties Special with Richard Goldstein and Norman Jopling.

Richard Goldstein was the rock critic of the Village Voice back in 1966 and has a claim to be the world's first rock critic. His memoirs, Another Little Piece of My Heart: My Life of Rock and Revolution in the '60s, record his wild times, hanging out with the Doors and Grateful Dead and going on the road with Janis Joplin.

Norman was the young hot-shot reporter on the Record Mirror back in the 60s, reporting on the Beatles and Stones when London was swinging and from the front line of the soul-inspired mod movement. His book's called Shake It Up Baby!. Mark Ellen has reviewed it (below) in The Oldie.

Go here to book tickets.

Saturday, March 07, 2015

The Carole King musical Beautiful has one trick but it's a damned good one

The script of Beautiful, the musical based in the songs of Carole King, her first husband Gerry Goffin and their friends and rivals Barry Mann and Cynthia Weill, reminded me of the tongue in cheek captions Mark Ellen and I once wrote to accompany the stories of the Human League and Shakin Stevens in the Smash Hits Yearbooks, so relentless is its commitment to exposition.

"This guy Dylan is making us seem so dated."

"There's this band called the Monkees".

"The dance crazes are still going strong. Couldn't you write a dance song?"

However if you want a jukebox musical then you'd best pick one where the jukebox is stocked with quality and nothing but quality. As a drama Beautiful relies on only one trick but it's a damned good one. Every song is introduced as a work in progress. The lead sheet is set out on the top of the piano, a couple of chords are picked out and there then follows an opening line which is written on everybody's soul.

"Tonight you're mine, completely..."

"What should I write? What can I say? How can I tell you how much I miss you?"

"You never close your eyes any more when I kiss your lips...."

"When you're down and troubled and you need a helping hand...."

"Everybody's doing a brand new dance now."

You can feel the same thought rippling down the row of seats. What, this one as well? I went with my daughter who simply couldn't believe that all these songs, which, of course, are every bit as familiar to her as they are to the people who lived through them, had come from this handful of people.

Is it corny? Yes, of course it is, but it's also true to King's story between the 50s and early 70s; there are points at which they must have been tempted to bend the facts to fit the requirements of drama but they've resisted, for which they should be given points.

The script is Gerry Goffin complaining that you can't possibly say anything meaningful in three minutes.

The music is Carole King proving again and again that you can.

"This guy Dylan is making us seem so dated."

"There's this band called the Monkees".

"The dance crazes are still going strong. Couldn't you write a dance song?"

However if you want a jukebox musical then you'd best pick one where the jukebox is stocked with quality and nothing but quality. As a drama Beautiful relies on only one trick but it's a damned good one. Every song is introduced as a work in progress. The lead sheet is set out on the top of the piano, a couple of chords are picked out and there then follows an opening line which is written on everybody's soul.

"Tonight you're mine, completely..."

"What should I write? What can I say? How can I tell you how much I miss you?"

"You never close your eyes any more when I kiss your lips...."

"When you're down and troubled and you need a helping hand...."

"Everybody's doing a brand new dance now."

You can feel the same thought rippling down the row of seats. What, this one as well? I went with my daughter who simply couldn't believe that all these songs, which, of course, are every bit as familiar to her as they are to the people who lived through them, had come from this handful of people.

Is it corny? Yes, of course it is, but it's also true to King's story between the 50s and early 70s; there are points at which they must have been tempted to bend the facts to fit the requirements of drama but they've resisted, for which they should be given points.

The script is Gerry Goffin complaining that you can't possibly say anything meaningful in three minutes.

The music is Carole King proving again and again that you can.

Thursday, March 05, 2015

Reality stands out like a sore thumb in the middle of something as fake as a football match

Swansea's Gomis collapsed during last night's game at Tottenham. There was no contact. He just went down as if poleaxed. Gomis has a history of similar fainting episodes. Following treatment, he was fine. He even wanted to carry on.

However you can see from Bentaleb's reaction in the picture how shocked the players were when Gomis went down and was suddenly surrounded by medical teams from both benches.

However you can see from Bentaleb's reaction in the picture how shocked the players were when Gomis went down and was suddenly surrounded by medical teams from both benches.

It always impresses me how quickly footballers know when something serious has happened on a football pitch and how instantly they drop all the play-acting. A genuine, potentially life threatening injury in the middle of a match is immediately apparent to all of them, no matter how far away they are from the action. They react with such shock that you'd think they were 12 year-old-boys rather than hardened athletes.

That's as it should be, of course. What's not as it should be is the pantomime of agony that takes up most of the average game and increases the nearer the top of the table the teams involved are placed. The intensity of faking in football has parted company with reality and can now only be compared to the death scenes in particularly overwrought operas.

As in the opera, nobody's convinced about the injury being feigned but it's just sort of expected. As one former-pro pointed out recently, nobody's who's hurt rolls over three times. If the players who went down were hurt as much as they claim to be their team mates would be rushing to get them help, rather than rushing to get somebody else booked.

The sudden arrival of actual jeopardy, as happened last night at White Hart Lane and at the same place in 2012 in the far more serious case of Fabrice Muamba, only makes the fake variety look more fake.

Sunday, March 01, 2015

When rock stars played Scrabble

The more I look at 1971 the more it seems like a vanished world. I've Always Kept a Unicorn: The Biography of Sandy Denny by Mick Houghton is an oral history made up of interviews with people who knew her and worked with her and it's full of telling details of that same old world.

I've just been stopped in my tracks by one such detail.

Sandy Denny and Trevor Lucas liked to play Monopoly and Scrabble.

There they were, a swinging young bohemian couple with famous friends and a Chelsea address, and they chose to spend their time playing Monopoly. (Bruce Springsteen and Steve Van Zandt were doing the same at the same time over in New Jersey.) And when there wasn't a board around they invented word games. That's where the title of Fairport Convention's third album "Unhalfbricking" came from.

This tells you one thing about life at the time and probably how that era came to produce so much vital music.

There wasn't a lot else to do.

In those days young, hip, long-haired people never watched television. They couldn't afford a set and there wasn't much to watch on it if they did.

Of course they lived full lives - drinking, socialising, fornicating, playing, plotting and all the rest that you might expect - but they didn't live with the low level distractions which are an inevitable by-product of plenty and progress. That is what made them so productive.

Next Monday, March 9th, Mark Ellen and I will be talking to Mick Houghton, who wrote the book, as well as Simon Nicol and Ashley Hutchings, who started Fairport Convention in 1967.

It's at the Slaughtered Lamb in Clerkenwell. It starts at 7:30 and is over by 9:00. You can find out more and get tickets here.

I've just been stopped in my tracks by one such detail.

Sandy Denny and Trevor Lucas liked to play Monopoly and Scrabble.

There they were, a swinging young bohemian couple with famous friends and a Chelsea address, and they chose to spend their time playing Monopoly. (Bruce Springsteen and Steve Van Zandt were doing the same at the same time over in New Jersey.) And when there wasn't a board around they invented word games. That's where the title of Fairport Convention's third album "Unhalfbricking" came from.

This tells you one thing about life at the time and probably how that era came to produce so much vital music.

There wasn't a lot else to do.

In those days young, hip, long-haired people never watched television. They couldn't afford a set and there wasn't much to watch on it if they did.

Of course they lived full lives - drinking, socialising, fornicating, playing, plotting and all the rest that you might expect - but they didn't live with the low level distractions which are an inevitable by-product of plenty and progress. That is what made them so productive.

Next Monday, March 9th, Mark Ellen and I will be talking to Mick Houghton, who wrote the book, as well as Simon Nicol and Ashley Hutchings, who started Fairport Convention in 1967.

It's at the Slaughtered Lamb in Clerkenwell. It starts at 7:30 and is over by 9:00. You can find out more and get tickets here.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)